Novel, Rapid Methadone to Buprenorphine (Suboxone) Switch Protocols

- bpk298

- Aug 6, 2024

- 12 min read

Updated: Aug 7, 2024

It is a common misperception that patients on methadone must be reduced to a dosage of 25 to 40 mg per day in order to be switched to buprenorphine (Suboxone). In reality, physicians around the world have had success with rapid, 5- to 7-day transition protocols that do not require reducing the methadone dose before buprenorphine initiation. I've compiled some review articles and clinical case reports to bring to your physician if he / she is not aware of the possibility of rapid transition from a full maintenance dose of methadone to buprenorphine (Suboxone).

Complete Metabolic Panel from ~ 48 hours into a 7+-day Cardiovascular Intensive Care Unit stay after a fentanyl OD almost killed me two years ago. The disruption of the acid-base balance of the human body, evidenced here by elevated bicarbonate, is one of the most dangerous results of an OD. Elevated creatinine indicates kidney stress / damage and possibly a form of muscle breakdown called rhabdomyolysis, which can occur during OD.

This hospital stay was when I decided to start this blog. I realized how long it was going to take to get published through the traditional route. I had so much to say about addiction, and the idea that I might just wick out without sharing any of it was suffocating (I think Thoreau is overrated, and maybe one reason that I'm not a huge fan is because my desperation is anything but quiet, and I refuse to take it to my grave).

Anyway, this hospital stay was also when a very kind, competent Nurse Practitioner introduced me to the possibility of rapidly switching from methadone to buprenorphine without having to taper almost all the way off of methadone first.

In Medias Res: The OD

If you are on methadone and it isn't working well for you and / or you are planning to get off of it, then the information that I will share today is potentially more useful than anything else on this blog.

In November of 2022, I was tapering off of methadone (which, for the uninitiated, has the most protracted withdrawal of any opioid drug and is reputed to be the hardest substance of all to get off of).

I did well for a while, but I pushed the dose downward too quickly, at which point I became too sick to run, at which point, predictably, a strong beam of reality dissolved my "mental health" like the gossamer veneer that it was.

I relapsed on fentanyl daily for maybe three weeks. Then, because getting off of methadone and onto fentanyl was clearly worse than pointless, I stopped the fetty for 11 days.

Then, because I'm an incorrigible drug addict, I used fetty one more time, at which point I collapsed on the side of the road near my dealer's (I still have no idea who called an ambulance for me, and - given that this was on the West Side of my home city, a ghetto where ODs are as common as sex scandals during American presidencies - I'm shocked that someone cared enough to ring an ambulance [my best guess is that the guy who sold it to me or one of his customers recognized me, but I lost that dealer's number, so I don't know for sure]).

Anyway, the point of all of this is that it is extremely difficult to taper from 100-180 mg of methadone / day to the 25 to 40 milligrams a day that almost all U.S. clinics have traditionally required you to reduce your dose to before you can switch to buprenorphine, which is in almost all cases a more effective and less sedating / intoxicating opioid maintenance medicine (I've written about the perils of methadone maintenance in Metha-Don't and about my deep discontent with opioid maintenance more generally in Sword of Damocles).

I could list the whole gamut of methadone withdrawal symptoms - it's like having the true flu for months on end - but the emergent whole is much worse than the sum of its parts.

When you're on a high dose of such a potent opioid for an extended period, your body comes to depend upon it at a subcellular level; your entire physiology is guided and permeated by the drug.

Being without your opioid substance of choice triggers a fish-out-of-water response that I, with my haughty literary pretensions, can only compare to the Dementor's Kiss in Harry Potter: It's as though all life, all hope, all energy and all goodness are sucked from the world.

For this reason, most people on methadone never get off of it. This is a shame on many levels, one of which is that many people on methadone would be more stable and experience fewer side effects if they could switch to buprenorphine (Suboxone).

The Science: Full and Partial Agonists at the Mu Opioid Receptor

If you need a review of mu opioid receptor dynamics, including full versus partial agonism, antagonism, and binding affinity, now would be a good time to consult my detailed walkthrough of what causes precipitated withdrawal. This is information that I recommend to anyone who loves, treats, or is an opioid addict because making informed treatment decisions without understanding these receptor dynamics is difficult to impossible.

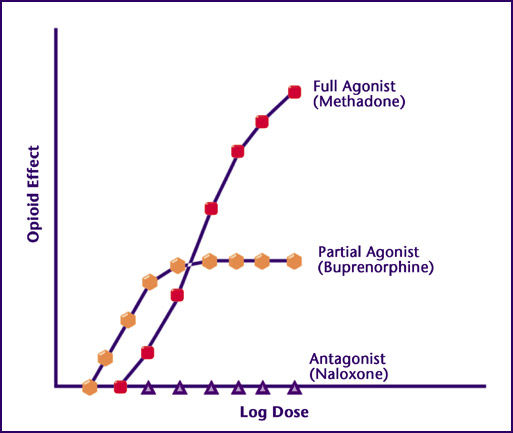

The amount of opioid receptor stimulation caused by a ceiling dose of buprenorphine is approximately equivalent to the opioid effect produced by 25 to 40 mg of daily, oral methadone. As a result of this, if someone dependent on a dose of methadone greater than 25-40 mg / day suddenly has their receptors flooded with buprenorphine, that person is going to experience precipitated withdrawal proportional to the gap in opioid stimulation caused by their methadone dose and the level of opioid effect produced by the ceiling dose of buprenorphine (see graph below for detailed explanation).

Methadone is a full agonist, meaning that as you increase dose, opioid effect (opioid receptor stimulation) increases indefinitely. On the other hand, buprenorphine (Suboxone) is a partial agonist, meaning that there is a ceiling dose beyond which further increases in dose will not result in more opioid receptor stimulation (opioid effect).

If you trace your finger from left to right until you get to the fifth purple triangle on the Antagonist (Naloxone) curve that runs along the x-axis (Log Dose), then go directly upward to the Full Agonist (Methadone) curve above, you're at a position close to the dose / opioid effect that most methadone maintenance patients are used to.

If, on the other hand, you start at this fifth purple triangle and go vertically upward to the Partial Agonist (Buprenorphine) curve, you see that the level of opioid effect produced by the partial agonist (buprenorphine) is significantly less than the opioid effect produced by the full agonist (methadone) at these dosage levels.

In fact, at any methadone dosage less than (to the left of) the point at which the buprenorphine and methadone curves intersect, which is approximately equal to 25 to 40 milligrams of daily methadone taken orally, there is a buprenorphine dosage that can produce an equal level of opioid effect. As long as this is true, you can switch from methadone to buprenorphine without experiencing significant withdrawal.

However, at dosages higher than the ceiling dose of buprenorphine (to the right of the point of intersection of the methadone and buprenorphine curves), which is equivalent to approximately 8 to 16 mg / day of sublingual buprenorphine, increasing the buprenorphine dose no longer results in increased opioid effect - you hit the ceiling effect, and the buprenorphine curve flattens out. If someone is dependent on a daily dose of methadone higher than 25 to 40 mg and you suddenly flood their receptors with buprenorphine, that person is going to experience precipitated withdrawal proportional to the vertical gap between the two curves.

Because of these receptor dynamics, most methadone clinics require patients to reduce their dose to 25 to 40 milligrams before they switch over to buprenorphine.*

*Patients are also typically forced to wait 2 to 3 days from their final dose of methadone before beginning buprenorphine, which is initiated gradually starting at a very low dose. Unfortunately, this highly uncomfortable switch protocol results in many patients relapsing, and - because of suddenly decreased tolerance combined with the lack of blocking action from buprenorphine or methadone - the overdose risk is exceptionally high in this timeframe.

The final key point about the relevant receptor dynamics is that the risk of precipitated withdrawal is greatly overstated in the case of switching from methadone to buprenorphine.

True precipitated withdrawal, which is capital "H" Hell on Earth, occurs when a person dependent on a high dose of a full agonist like heroin or fentanyl is suddenly given an antagonist such as naloxone or naltrexone, which blocks all opioid receptor stimulation, resulting in a sudden drop from 120 mph to 0 mph.

At worst, dropping from a high dose of methadone to a ceiling dose of buprenorphine is like dropping from 120 mph to 45 or 60 mph.

The opioid receptors are still receiving substantial stimulation, and - depending on how high a dose of methadone the patient was dependent on - the withdrawal effects are likely to be mild or moderate (thoroughly tolerable, in other words).

Rapid Transition Protocols (AKA the Future)

For those of you who prefer to review the literature directly, here is an excellent review article that contrasts the methadone to buprenorphine switch protocols used in several countries, including Canada, the UK, and the U.S. (both the American Society of Addiction Medicine [ASAM] and Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration [SAMHSA] guidelines are presented for the US).

As you will see, all of the protocols save for New Zealand's recommend that the patient first reduce his / her dosage to 60 mg or below, and most recommend 30 mg or less with a gap of 24 to 72 hours between stopping methadone and initiating buprenorphine.

These traditional protocols made theoretical sense because reducing the methadone dose to one that provided a level of opioid effect equal to that produced by a ceiling dose of buprenorphine ensured that there was no withdrawal caused by the transition; the body was receiving a stable level of opioid receptor stimulation.

However, as mentioned above, the requisite reduction in dose was very difficult for patients to achieve, often necessitating several weeks of moderate to severe withdrawal symptoms before he or she could switch from methadone to buprenorphine. As noted above, relapse - particularly during the 1- to 3-day gap between the last methadone dose and the first buprenorphine dose - was both common and particularly dangerous.

These protocols proved to be excessively conservative for multiple reasons.

The first is that the body can tolerate some sudden drop in opioid receptor stimulation. Especially when comfort meds like gabapentin and clonidine are provided to smooth the switch, even the withdrawal experienced by someone transitioning to buprenorphine from a daily methadone dose of 100 mg or more is not too severe to be tolerated.

The second is that the transition happens gradually, avoiding precipitated withdrawal by allowing the body some time to compensate; this is because methadone clings to the receptor tightly and has a long half-life, meaning that as buprenorphine is introduced at increasing dosages, methadone gradually relinquishes its hold on the receptors - resulting in a smooth, balanced transition rather than an abrupt, one-time drop.

***

"We can have you switched from methadone to buprenorphine in 3 to 5 days; you'll be stabilized on it before we discharge you," Sandra, a Nurse Practitioner at the teaching hospital in my home city, assured me; she had the subtle highlights and the kind and comely confidence of the archetypal MILF.

Sandra had noted that the methadone that I was taking simply wasn't holding me; my body eliminated it much faster than the average person's, probably because of the synthetic thyroid hormone that I take due to my Graves' Disease. As a result, she observed, I was in significant withdrawal by midday, meaning that I was a better candidate for buprenorphine maintenance.*

*Buprenorphine tends to produce a more stable opioid effect because of its properties as a partial agonist.

What Sandra was offering sounded too good to be true.

All of the staff at my methadone clinic had reiterated the recycled wisdom that the only way to switch from methadone to buprenorphine was by first reducing one's methadone dose to 25 mg a day. Unfortunately, I was currently in the ICU because I had experienced a near-fatal fentanyl overdose during my attempt at this long, brutal taper.

"We've had several patients do it, and we've never had one fail," Sandra insisted.

"Did they have awful, precipitated withdrawal symptoms, though?" I followed up.

"Not at all," Sandra replied. "Some pretty bad GI stuff, for one patient, but we were able to treat it with loperamide. Headache, anxiety, and insomnia for a couple others - treatable with gabapentin and in one case a benzo for a few nights.

"None of our patients ended up going back on methadone," she continued, "and the only one who relapsed on his drug of choice was able to stop using it within a week of starting buprenorphine."

It turns out that the 25 to 40 mg reduction rule - a safe, sensible limit that was established based on a solid theoretical understanding of the mu opioid receptor dynamics - is in reality unnecessary and harmful.

As I completed my research, I read European studies from the past decade in which buprenorphine treatment was rapidly initiated over the course of several days in patients dependent on methadone doses ranging from 40 mg / day to over 100 mg / day. All of these patients were successfully transitioned to buprenorphine, and none of them required emergency treatment for catastrophic withdrawal.

In this case, conventional wisdom was plain wrong; it was overly conservative and underestimated the body's ability to rapidly adapt to changing levels of opioid receptor stimulation.

For those of you who are clinicians hoping to begin using a rapid transition protocol - or patients hoping to raise the possibility with your physician or other provider - here is a wonderful article that summarizes rapid transfer protocols for high-dose methadone patients; it covers microdosing as well as the use of medications to smooth the transition (including lofexidine, an alpha-adrenergic agonist similar to clonidine).*

*This portion of the results presented in the paper was summarized as follows: "In general, transfer from methadone 30-70 mg to buprenorphine was found to be relatively uncomplicated and can be facilitated by lofexidine."

Because the ease of the transition depends on gradually ramping up the buprenorphine dose while gradually reducing the methadone dose, some of the protocols initiate buprenorphine treatment with transdermal patches, which smoothly deliver a much lower dose of buprenorphine than sublingual formulations typically provide.

In some protocols, transdermal fentanyl and other short-acting, full-agonist opioid medications were used as bridges between methadone and buprenorphine.

In certain protocols, withdrawal was briefly (!) precipitated with naltrexone prior to switching to a short-acting, full-agonist "bridge" opioid or beginning buprenorphine treatment.

For further support, here is another protocol in which withdrawal was intentionally precipitated with naltrexone before initiating treatment with buprenorphine.

Summary

The reality is that you can be switched from a full maintenance dose of methadone to buprenorphine in 5 days without experiencing severe withdrawal.

It is possible that you will need comfort medications to ease the transfer, but it is very unlikely that you will suffer severe, precipitated withdrawal* of the sort brought on by sudden introduction of an antagonist into the system of a person who is dependent upon a full agonist like methadone, heroin, or fentanyl.

*Except for the protocols that intentionally precipitate withdrawal with naltrexone, which is done very briefly before fentanyl or another full agonist with a very high binding affinity is administered as a bridge between the methadone and buprenorphine.

It is a sad testament to the reactionary, overregulated nature of psychiatry and addiction medicine in the U.S.* that so few clinicians at methadone clinics know about these rapid transition protocols.

*I'm not sure how it works in other countries, but in the U.S., these specialties are among the lowest paid, and they draw med students with low Step 1 board scores - i.e., few well-paying / competitive residency prospects.

Despite the fact that they have been under investigation for years, many doctors and nurses at U.S. methadone clinics aren't aware of them, and exceedingly few programs offer them to patients.

If you're not able to switch to buprenorphine because the long, intense taper down to 25 to 40 mg of methadone per day is too much for you, there is hope!

You should absolutely raise the possibility of an alternate switch protocol with your doctor, Physician Assistant, or Nurse Practitioner. (I recommend printing out and bringing the review articles that I referenced / linked above! If you do most of the work for them, you have a greater chance of getting them to agree to a different protocol.)

Alternatively, contact the psychiatry / addiction medicine department of the teaching hospital in your area - the one affiliated with a nearby research university.

It is almost always the case that such hospitals will be the most policy-progressive, technically advanced, and least risk-averse clinical facilities in any given region (in my home city, where three groups operate methadone clinics, none of them offers a rapid transition protocol; only the teaching hospital does so, and the staff at the methadone clinics aren't even aware of this).

Of course, if worst came to worst and you were suddenly unable to obtain your methadone for some reason, an adapted, at-home version of these rapid transfer protocols could be employed.

As always, I'm available to answer questions about individual situations via the "Contact" form on this site or the Concrete Confessional Instagram. I don't provide medical advice; I simply share my own ideas and experiences - to be followed up on with your provider.

I am receiving so many questions about tapering and withdrawal these days that I've been joking about starting a high-end "opioid / benzo withdrawal doula" consultancy.

There is hope. We do recover. Please, be well.

Comments